Whilst making my Encounters Series, I visited St Petersburg and the famous Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood to research Russian Orthodoxy. The beautiful domed building, inspired by medieval Russian architecture, houses over 7,500 square meters of glistening mosaics and an exquisite iconostasis made of the finest Italian marble. I was particularly drawn to the icons in the South Stand depicting the Mother and Child - Our Lady of Kazan and Theotokos of Tikhvin. I was really intrigued by the removal of the hands and faces, particularly because they were now black. I was informed that in this instance the paint had worn away over time, and had darkened because of the soot from the votive candles used in Church services. I chose to use the icon in my portrait Encounter, Ruby. When I made all of the pieces in Encounters, I was really inspired by the removal of the faces as well as the use of gold and rich ornamentation all over the building and the icon cases carefully constructed with precious metals, jewels and gems.

When I got back to London I was still curious and thought these black icons were so visually interesting, that I had to do some more research. It was at this point that I came across the so-called Black Madonnas. Examples of the Black Madonna may be found all over the world. I wondered, given the pervasive legacy of the whitewashing of the holy family, whether the black can be read as a signifier of ethnicity or was there some other historic, cultural or semiotic meaning?

Of course, in many cases, Black Madonna’s are deliberately created in the image of the community in which they will be used, for example, there are a plethora of images of Mary intentionally depicted as a Black woman, and Black Madonna’s were often sent to Latin America by colonialists in an attempt to appeal to local populations and convert them. However, according to some estimates, there are around 500 Black Madonnas in Europe alone, mostly Byzantine icons and statues of Medieval origin in Catholic and Orthodox countries. Their darkness is not understood as sinister or evil, but they are seen as powerful, peaceful and inherently good. They are highly venerated and many have received divine approval manifested by their reputation for an association with miracles. But they have a complex history and many different interpretations.

Scholars have argued that - much like the icons I saw in the Church of the Spilled Blood - the skin had darkened from exposure to candle smoke, fire, or other cosmetic factors. The statue of Our Lady of Altötting was rescued from a church fire in the 10th century. The Our Lady of the Hermits, from Einsiedeln was damaged during the French occupation in the 18th century and restored with white skin, (however, the congregation were outraged and demanded it be painted back to black!).

There are many others who argue that the dark skin tone is, in fact, intentional. Some suggest a connection with ancient and pagan earth or mother-goddesses such as Gaia, Demeter, Isis or Cybele, linked it to the Jungian archetype of the Dark Mother, or a combination of Eurasian, Native American, and African cultures. The black was associated with fertile earth but can be seen as an expression of an ancient cultural memory that connects us back to our early history in Africa. The Lady of Regla from Cuba has been explained as an African Deity synchronised with Catholicism and exported as part of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The Black Madonna perhaps represents a curious exception to race and blackness in medieval art. Elisa A. Foster argues that the Virgin of Le Puy in Auvergne ‘presents a significant example of the multivalent nature of both Marian iconography and skin colour in pre-modern Europe ... Blackness in the case of the Virgin of Le Puy then was a symbol of antique Eastern origin rather than race or ethnic difference. It can be reasonably proposed that the medieval statue of the Virgin of Le Puy was deliberately painted black in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century in order to conform to a newly invented Egyptian provenance’.

Another explanation associates the Black Madonna with a biblical verse, stating that it refers to the words of the Bride in the Song of Solomon: “I am black but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem.” This theory establishes a clear intention behind the blackness of the image but has not been well substantiated.

Despite all of these possible theories the Black Madonna has been adopted as a symbol of national identity, resistance against oppression, and racial and female empowerment. I choose to see it as an extraordinarily powerful and captivating image as well as a deep and enduring cross-cultural expression. Let me know what you think in the comments!

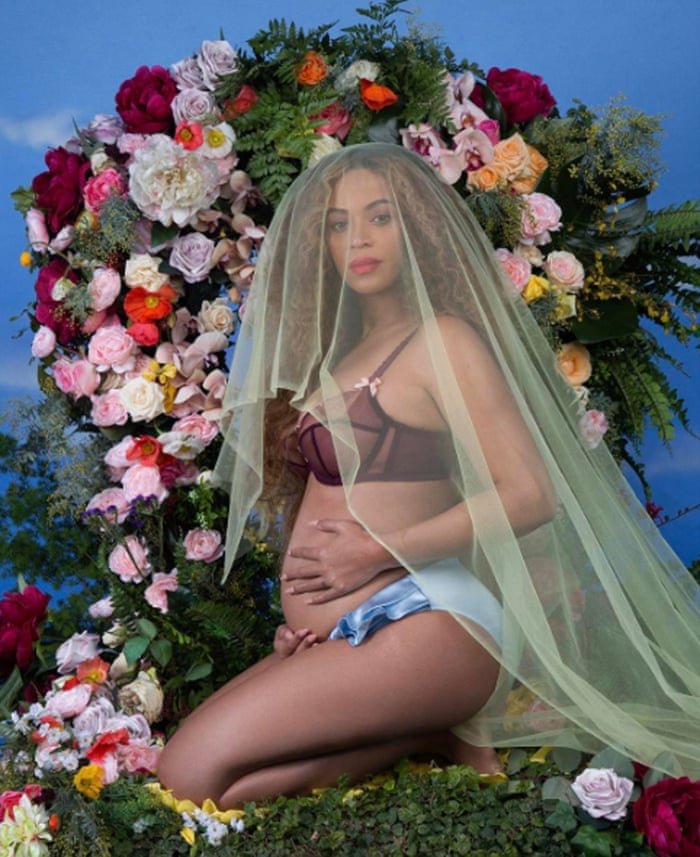

I couldn’t leave out the Queen of religious and art historical references Beyonce! Her portraits below - by Awol Erizku and Mason Poole respectively - raise questions of motherhood, divinity, and race and reclaiming the imagery of the Madonna and Child giving it a profound new meaning.